The Henry Kissinger Paradox, Israel’s Nuclear Doctrine, Iran, and the War in the Middle East

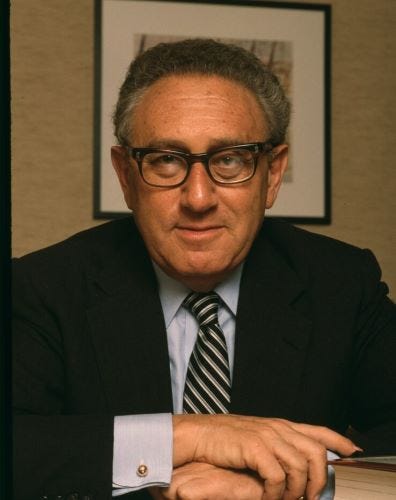

A few months ago, Henry Kissinger died at the age of 100. The world’s newspapers were filled with obituaries of one of the 20th century’s most influential statemen. The Otto von Bismarck of the modern era. The homage written to him by Aluf Benn, editor-in-chief of Ha’aretz was unusual and surprising. Entitled “Kissinger's Power-over-progress Paradigm Found Attentive Ears in Israel”, Aluf Benn’s article focuses on Kissinger’s most significant contribution to the strategic relations with Israel that continues, in his opinion, to this day: the unique status and protection that the US grants Israel on the nuclear issue. What is known in the nuclear jargon as “Israel’s nuclear ambiguity doctrine”.

In this obituary, the Haaretz editor-in-chief refers to the 1969 “Nixon-Golda Understandings” which provides Israel with an exemption from obeying international norms for preventing nuclear proliferation. According to these secret understandings, which were formulated by Kissinger, then the US national security advisor, Israel would not declare that it possesses nuclear weapons, and would not carry out nuclear tests. In return, the US administration would no longer demand that Israel sign the NPT, the treaty that is a central component of US nuclear non proliferation policy. Aluf Benn summarises by saying that in this way “Kissinger enabled Israel to retain Dimona even as the U.S. was taking action to thwart the nuclear ambitions of other friendly countries”. The secret Nixon-Golda understandings were only revealed many years later.

Israel’s special nuclear status was granted in the historical context of superpower confrontation against the Soviets during the Cold War. Israel was perceived by Kissinger as the West’s forward post. The nuclear ambiguity doctrine did indeed provide Israel with a unique nuclear status that was considered an exceptional achievement in the Israeli security doctrine. Israel could have the best of all worlds: attain strategic deterrence without having to declare it publicly and without having to pay the political price in international forums.

In this article, I will try to revisit Aluf Benn’s nuclear argument. The history of the Israeli nuclear issue usually remains hidden from the public discourse. We can always learn something new by taking another look at history. We will try to clarify whether the security doctrine that was determined 50 years ago in cooperation with the US is still valid today and if it is possible to continue with it in the new international environment. In my analysis, Israel’s unique nuclear status was not automatically granted and continuous as is generally thought. Over the years, there have been fluctuations and prices were paid. Trends of limiting US support that could return today with the emergence of Iran as a nuclear threshold state, and the danger of a widespread regional war following the 7 October Hamas surprise attack.

The prevention of nuclear proliferation is one of the US top national and security policy’s goals. In spite of the “Nixon-Golda Understandings”, the US had to act on this issue also vis-à-vis Israel. Therefore it took seriously the declaratory policy part of the ambiguity doctrine and strove to create Israeli commitment on this issue. Starting with the meeting between Shimon Peres and President John F Kennedy and the promise that “Israel will not be the first to introduce weapons in the Middle East”, and continuing with the relationship between atom and peace. This was reflected in a package deal by which Israel presented in international forums its readiness for a Middle East nuclear free zone on condition that the disarmament would include regional monitoring mechanisms for the countries in the region (following the Latin American Tlatelolco Treaty model) and given peace treaties and mutual recognition with Arab states.

Israels’ conditions for a Middle East Nuclear Free Zone were part of Israel’s “long corridor” concept whose goal was to avoid reaching the final door labelled NPT. But this has not prevented the US from, over the years, presenting proposals for a Middle East disarmament that were not agreeable to Israel. For example, the Bush and Clinton initiatives for interim nuclear steps by including Israel in the proposed Fissile Material Cut-Off Treaty (a treaty that has been stuck for many years in the Conference on Disarmament in Geneva). Or President Obama’s support, which surprised Israel, of the Egyptian proposal (including the nomination of a Finnish diplomat as mediator) for the convening of the Helsinki conference for the creation of Middle East Nuclear Free Zone.

International efforts for nuclear weapons disarmament are always on the table. In spite of the retreat from these efforts by the Trump administration which abandoned international nuclear agreements, and Putin’s aggressive nuclear rhetoric during the war with Ukraine. These efforts could return in the Middle East regional context. Since the unlimited extension of the NPT in 1995, the creation of a Middle East Nuclear Free Zone has been a substantial fourth pillar of the Treaty together with the pillars for the prevention of nuclear proliferation, nuclear disarmament, and the use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes.

The tight linkage between US peace policy and nuclear disarmament worries Netanyahu. In parallel to expressions of opposition to US peace initiatives, he is also working to undermine or at least to dilute Israel’s traditional nuclear ambiguity doctrine. In the first stage, to eliminate the declaratory policy which is an inseparable part of the ambiguity doctrine, and sending signals regarding a transition to overt nuclear deterrence. To begin a move to a new nuclear situation on the declaratory level. The most explicit expression of this was at the ceremony marking the inauguration of the Shimon Peres Nuclear Research Center in Dimona in 2018. The emphasis in Netanyahu’s speech was the role of deterrence in the face of existential threats. The Prime Minister chose to speak at this particular place in order to disconnect himself from the declarative “we will not be the first” element that was identified with Shimon Peres, and to replace it with a nuclear tinged message to Iran: “whoever threatens us with destruction puts himself in similar danger”. Remember that in the Israeli system, the Prime Minister is the head of the Israeli Atomic Energy Commission which is responsible for nuclear policy.

If Netanyahu had thoughts of a gradual withdrawal from the nuclear ambiguity policy to overt deterrence, the surprise Hamas attack that led to the longest and most intensive war in Israel’s history since the 1948 Independence War, created unexpected circumstances for him and for the US. In particular, when Iran became, as a result of the collapse of the JCPOA, a nuclear threshold state with latent military nuclear capability. This is a state of strategic uncertainty and new circumstances that may create dangerous ground for escalation between Israel and Iran in the nuclear field. For the first time, a potential has been created for a military confrontation with a nuclear dimension in the context of two rivals in the Middle East. In the Yom Kippur war, the nuclear dimension was one-sided.

The increasing Iranian assertiveness in the nuclear field as it is reflected in the latest IAEA reports has brought the Biden administration to act, from the first day of the war, to thwart an escalation dynamic between Iran and Israel. This was reflected in the US warning message of sending aircraft carrier task forces to the region with tens of fighter jets. The goal was to remove from the minds of Iranian planners any thought of breaking out to nuclear weapons and the renewal of the weaponization program that was closed in 2003. In order for the message to be as clear as possible, the US also made sure to transmit it on the verbal diplomatic level via a back channel at the Swiss Embassy in Teheran (a channels that exists to this day) and indirect discussions from time to time with Iranian representatives in Oman.

It would appear that the US deterrent message to Iran has been clearly received. As I wrote in a previous article, contrary to the gloomy assessments of some commentators, it seems that Iran did not exploit the opportunity provided by the war to race to nuclear weapons. The US DNI report that was presented to President Biden (February 2024) determined, in the opening lines of the section on Iran, that “Iran is not currently undertaking the key nuclear weapons-development activity necessary to produce a testable nuclear device”.

The US deterrent message also played a double role vis-à-vis Israel. Providing the ultimate guarantee for Israel’s security during its dark hour. To provide the Israeli leadership and society with a feeling of security following the 7 October Hamas surprise attack and the blow to Israel’s traditional security doctrine. And at the same time, to calm Israel in order to prevent it from taking unilateral steps. To ensure that Netanyahu does not intend to exploit the military escalation in order to implement the “Begin doctrine” of an Israeli first strike that would drag the US into attacking Iranian nuclear sites. This is an old dream of Netanyahu, and an age-old US fear.

And there was another unseen latent element. A concern of the US, whose intelligence agencies were aware of Netanyahu's nuclear ideas, that the trauma of the surprise attack on October 7 could push the Prime Minister to make a shift in Israel's traditional nuclear ambiguity policy. Not necessarily within the parameters of a “demonstration” scenario such as the Moshe Dayan model on the second day of the 1973 Yom Kippur war, but the possibility of crossing a low nuclear threshold that would also be fraught with dangers: abandoning the declaratory doctrine of “we will not be the first” and replacing it with a declaration of a transition to overt nuclear deterrence. This would immediately bring about the collapse of the “US-Nixon-Golda understandings” policy. This could lead to the military acceleration of Iran’s nuclear program, the nuclearization of the region, and a nuclear arms race in the Middle East.

Within days of the Hamas surprise attack, we saw a leap forward in the special relations between the US and Israel, and an unprecedented dramatic reinforcement of the defense capability and deterrence granted by the US. But it is not sure that this will be sufficient in the face of the serious damage to Israel’s security concept. In the face of cracks at the heart of Israel’s security credo that it can defend itself by itself against any threat. It appears that Israel will need a formal defence alliance with the US to repair its deterrence, and defense of its territory against a massive attack. But this brings us to what I would call the Kissinger paradox. The US could sign a formal mutual defense alliance on the model of those with Japan and South Korea only if Israel joins the NPT as a “Non Nuclear Weapon State (NNWS)” as is defined by the Treaty. With the Kissinger understandings agreement, Israel received a US exemption from the NPT. A formal defense alliance would require a dramatic conceptual change in Israel’s traditional nuclear ambiguity doctrine.

Shemuel Meir is an independent Israeli strategic analyst. Graduate of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) and a former IDF and Tel Aviv University researcher.